Atlantis on the Charles

Too few people understand how Harvard functions, and this must change for its own betterment

Harvard is off to a rocky start in 2024.

President Gay resigned, and now both external observers and alumni are taking a more in-depth, critical look at the the whole institution. Those inside Harvard are responding with varying degrees of competence.1 You can see the battle lines being drawn in the sand from space.

As for my own part, I’ve been a strong, solutions-oriented critic of Harvard College’s government concentration (structurally and substantively), and I will continue to be.

But Harvard must be pulled from its current spiral and set on a firmer foundation. It is a great American institution, and no one should be excited to see it deteriorate, let alone “fall.” Alumni have a vital role to play here if they choose, and I hope they will join me in doing so. Plenty have recently registered interest in the current Board of Overseers elections, but productively engaging in institutional reform requires deep knowledge applied over the long term.

And knowledge about Harvard and its governing structure is, ironically, what Harvard alumni lack, especially where and how they fit into that picture. This is one root of Harvard’s malaise: an inability to tap the talent in most of its alumni network. By failing to engage its alumni, Harvard undermines its own governance structure, which presupposes robust alumni involvement.

This will only be reversed if: (1) more alumni bootstrap institutional involvement, and (2) the Harvard Alumni Association / Board of Overseers develops more outreach ability. The second one will inevitably be slower, if it comes at all, so it’s up to alumni in the short term to develop more groups, structures, and knowledge to eventually marry with their alma mater. This newsletter is one such endeavor.

But before I go further, let’s take a brief look at Harvard’s governance structure.

Alumni in Harvard Governance

Harvard has two governing boards, which is atypical. One is the President and Fellows of Harvard College (“the Corporation”), and it has the standard duties you’d expect a regular corporate board to have; it makes larger decisions and keeps fiduciary guardrails up. Harvard alumni do not vote for people on this board.2

The second is the Board of Overseers, which is an idiosyncratic feature of Harvard; alumni populate this one completely via elections. As far as the Board of Overseers is aware, this is unique in the world of higher education.3

The Overseers have a few hard powers, like the ability to give consent to any university presidential appointment (not insignificant!), but much of what they do lives in the realm of soft power.4

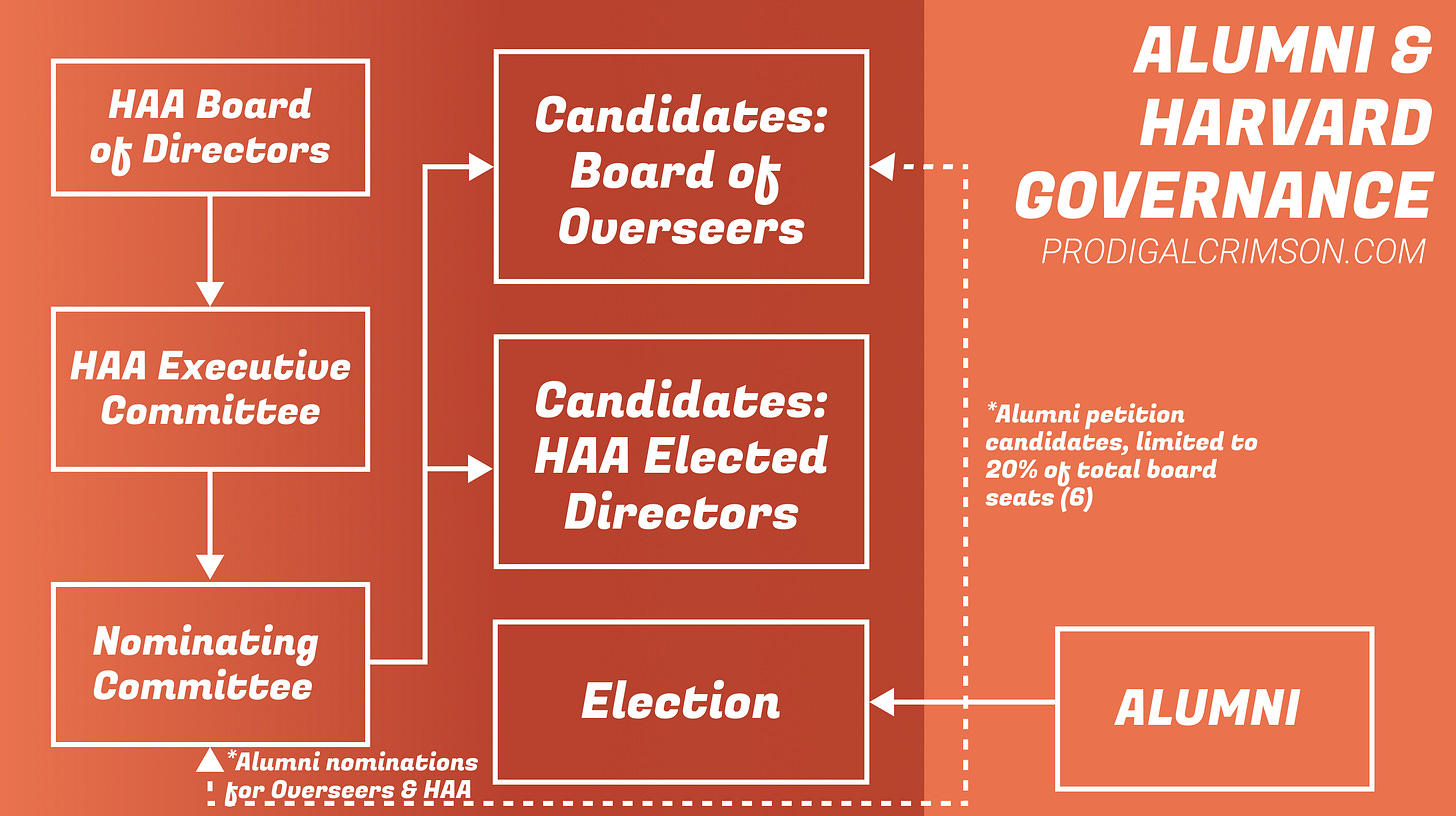

Sitting beside the two boards is the Harvard Alumni Association, which has its own vast internal structure. As far as alumni in Harvard governance, the Board of Overseers and the HAA are the primary entities of concern. They are the two mechanisms by which alumni wield power and influence, and the HAA largely controls the composition of the Board of Overseers. But if you’re not in either of these organizations, your power is strictly limited:

Given this governance map, a few things jump out:

Alumni have indirect influence on who ends up on their ballots by submitting nominations to the HAA Executive Committee’s nominating committee. Nominations are currently open for the May 2025 elections until May 31, 2024.

Alumni have tightly circumscribed direct influence on who ends up on their Board of Overseers ballots. They can put candidates on the ballot via petition (gathering the signatures of at least 1% of eligible voters), but there can be no more than 6 serving on the Board at any one time (out of 30 seats). If there are six at the time of an election, no petition candidates would be accepted.

Most of the direct power to populate the Board of Overseers lies with the Harvard Alumni Association, via their executive committee and its nominating committee. The nominating committee is made of 10 alumni selected by the executive committee, and three current or recent Board of Overseers members.

If alumni want to influence Harvard’s governance, they can wait to be nominated to join it, or they can try to join the HAA’s superstructure through a variety of paths.

OK, fine—if concerned alumni want to get involved to help change Harvard for the better, they can work their way through the HAA and try to get on the Board of Overseers. What’s the problem?

The problem: it’s simple enough to say that, but in practice both the HAA and the Board mostly fail at actually informing alumni of these options. Most alumni don’t understand either organization, and they are too busy with their lives to independently bootstrap an understanding of it. But it’s the HAA’s job to engage alumni, and the Overseers know Harvard alumni don’t understand it—yet nothing changes. Either incompetence, indifference, or malice is at play, and any warrants large change.5

In effect, or in fact, they ensure a smaller, more self-perpetuating group retains control. This could be OK—we have many closely held, private corporations in the U.S. that benefit from that structure. But I think the modern era shows that Harvard does not, just like a gene pool would not.

Alumni Are Locked Out of Governance—with Plausible Deniability

I have three important contentions here:

Harvard (the HAA and the Overseers) does not productively engage with the overwhelming majority of its alumni, and

It does not have the capability to do so, and

This undermines the legitimacy and quality of its governance structure.

For many people, these are surprising, possibly shocking, claims. What do you mean Harvard doesn’t engage with its alumni? And how on Earth can it lack the capacity to do so, it’s Harvard. Let’s look at alumni voting rates for the Board of Overseers, what those indicate, and the problems they cause.

Alumni voting is down, and has been down for a while

Harvard alumni have a terrible voting rate6 to rival the worst in American public office. From The Harvard Crimson in May 2023 (emphasis added):

Low voter turnout continued to plague the election, with a participation rate of less than 8.11 percent. More than 400,000 Harvard degree-holders were eligible to vote, but just 32,440 ballots were cast in the Overseers election.7

To my knowledge, Harvard doesn’t publish aggregated vote counts across time—or if they do, it’s not obvious. I created the graph below by reviewing election announcements from the Harvard Gazette, Harvard Magazine, and The Harvard Crimson.

In the modern era, Harvard has introduced many changes to its Board of Overseers elections. I indicate two on the graph above: (1) in the 2016-2017 election, Harvard began allowing candidates who want to get on the ballot by petition to collect signatures online, and they raised the number of signatures needed to do so to 1% of eligible voters; (2) In 2018-2019, Harvard began allowing alumni to vote online.8

And while this graph might make it seem like voting rates are trending up over time, even if slowly, that’s not true. You need to know the denominator (eligible alumni voters) as well as the numerator (number of votes cast). The 2016 elections had a 13.5% voting rate (35,870 votes from about 265,000 qualified electors)9, but by 2023 the rate had fallen into single digits again (see the Crimson quote above, at 8.11%).

Harvard seems utterly incapable of increasing its alumni voting rate, and even the absolute number of ballots cast seems beyond their influence. This is a good proxy for their inability to summon most other kinds of involvement.

Note: there is a numeric discrepancy here. The Board of Overseers requires at least 1% of eligible alumni voters to sign a petition to successfully get someone on the Board of Overseers ballot. Sam Lessin, a petition candidate, posted an email from Harvard indicating that this 1% threshold was 3,238. This implies an eligible alumni pool of 323,800. But the Harvard Crimson and Harvard itself both say Harvard has ~400,000 alumni, which has an implied 1% threshold of ~4,000. Who's right, who's wrong, and why? Read more >>

What do alumni voting rates tell us?

On one hand, some people say something like “alumni do not care about participating in Harvard governance.”

On the other hand, people point out all the hurdles that Harvard puts between its alumni and participating in the Board of Overseers election process. For example: until recently, elections were conducted by paper. Even now, the online elections are not straightforward; you need to update your HarvardKey account, which—I must say—was worse for me than any experience registering to vote in a public election.10

I think both of these perspectives, while getting at part of the truth, miss a central point: the Board of Overseers knows that alumni do not understand it, they aren’t capable of fixing it, and they seem insufficiently alarmed at both the prevailing alumni ignorance and their own impotence. From the conclusion of a 2020 report the Board issued (emphasis added):

…we note our view that all alumni would benefit from knowing more about the role and composition of the Board and the work of the Nominating Committee. We say this recognizing that the HAA, the associated alumni organizations across Harvard’s schools, and the University’s leadership already engage in a wide range of efforts to stay connected with alumni, to invite their perspectives, and to keep them informed about important issues and developments at Harvard. In our experience, both the distinctive role of the Board, and the thoughtful and diligent efforts of the Nominating Committee to identify outstanding candidates for the Board, tend not to be well understood across Harvard’s large and varied alumni community. We are pleased to see recent efforts to inform the alumni about both. We encourage further such efforts. And we hope that increasingly many alumni will take the opportunity to vote each year in the election for new Overseers.11

Hope will not raise alumni voting rates, which are obviously in the tank, or teach alumni. Whatever the Harvard Alumni Association and the Board of Overseers have been doing to change this, it’s been a failure. And this is the failure that must be examined and dug into.

Blaming alumni for not being engaged is too easy. It’s like government officials or activists blaming “voter apathy” for low voting rates or citizen ignorance about how the government works, while also utterly failing to present an engaging case for voting or understanding.

I have skin in the game here. I founded a civics school called Maximum New York aimed at solving NYC’s governance issues, and a principal component of my pedagogy says that civics instructors must be so good that they can outcompete Netflix. They must compel interest in their subject through their brand and classroom performance.12 I am no stranger to solving this hard problem. Happy, engaged students (busy professionals in NYC) take my classes in increasing numbers.

As I previously wrote to government officials, I now write regarding the Board of Overseers and the HAA:

Apathy might be at play here, but it’s often the apathy of the pre-technologic person who looks at a dead cell phone and tosses it aside, not some callous lack of civic virtue. The voter apathy lens scolds this person for not understanding the cell phone’s potential, but does not provide the relevant context to arrive at that understanding.13

So what do alumni voting rates tell us? That the Board of Overseers has failed, and is actively failing, to: engage alumni, explain themselves to alumni, get alumni to participate in the alumni governing board, and more. Alumni voting rates and lack of engagement, along with any legitimacy issues that arise therefrom, are to be laid almost entirely at the Board’s feet.14

To the institutionalists

If you are inside an institution, you’ve experienced people on the outside—who do not appreciate its realities—making demands about what you should obviously do. In our current moment, those who have done excellent work on behalf of Harvard might justifiably air some frustration about this phenomenon. Everyone wants to command you, but hardly any of them could explain the realities and constraints you face.

I have three things to say to you:

First: I see you. I read your work. I appreciate that you are the ones who work and show up, and that many of you do an excellent job. I know several of you personally. This is analogous to the NYC political world, which I’m part of.

Second: Harvard, by failing so completely to engage with most of its alumni, has removed most viable onramps for them to understand and participate in the institution. Institutionalists cannot pull up the ladder, by incompetence or malice, and then get mad that outsiders can’t climb it. It is primarily incumbent upon you, the insiders, to get much better at engaging alumni, not the other way around. It is literally your job.

Third: If you truly love Veritas, you will recognize that, clearly, you cannot do what needs be done by yourself.15 You need to pull from the untapped, vast reservoirs of talent in the alumni pool. Many things need to change, and you cannot change them—you are too few, and those inside Harvard who don’t want good change are too many. So become more.

And who better to help usher in change than you who’ve dedicated yourselves to Harvard, who appreciate its institutional peculiarities, and who possess the bulk of the intellectual dark matter that makes that institution run?

It’s up to you whether you will allow needed change, or continue to invite outside reprisal and internal incompetency by fighting it. I hope you will not choose the path of the inadequate advocate for such a great, important American institution.

To the reformers

You have a great vantage point untainted by status quo bias. You can more easily judge Harvard by the large, emergent effects of its many policies and internal politics, rather than becoming myopically focused on palace intrigue.

Truly, you are a wonderfully talented group of people.

And I have three things to say to you:

First: you do not know enough, and you need to know more. About Harvard’s history, about its corporate evolution, about its current administrative structure, about the soft-power flows on campus, and more. Creating a viable, long-term theory of change requires this knowledge. Even though crises open up moments of opportunity for reformers—and we’re potentially in such a moment—the kind of change Harvard needs is not one-and-done. It must be sustained for a long time, supported by knowledge and wisdom. But I’m not just throwing a mandate at you—the point of this newsletter is to help you learn all of those things (I need to learn more of them myself, as even do people inside Harvard).

Second: you do not currently know all the ways that institutional change can be achieved. You are likely at your most ignorant and least inspired right now. There are far more novel affordances than you can imagine from your current vantage point, so don’t index on your current levels of optimism or anticipation of difficulty.

Third: you must begin to participate in Harvard as an institution, if you haven’t already. This action gives you the insight and trust necessary to bring about your desired change. But if you’re most alumni, you don’t actually know how to do this, and Harvard doesn’t really help you! Never fear. Let’s do it together.

VERITAS VULT

For example (unfortunately there are many), Professor Hochschild did the Government Department, the Extension School, and the wider university a great disservice with her clumsy, reactive tweeting. You can review her profile for the full suite of expression, but the two important examples are this:

On Rufo: what do integrity police say about his claim to have “master’s degree from Harvard,” which is actually from the open-enrollment Extension School? Those students are great - I teach them- but they are not the same as what we normally think of as Harvard graduate students —this tweet from January 5, 2024

Followed by this:

I was asked to clarify, and am glad to do so: HES courses are Harvard U courses (often the same as in FAS, as for my courses). HES bachelor’s and master’s degrees are Harvard U degrees. HES is a school in Harvard U analogous to other schools. HES students are Harvard U students —this tweet from January 12, 2024

For an excellent run-down, I recommend reading “The Real Harvard Scandal” in The Atlantic, by Tyler Austin Harper (emphasis added):

The conservative activist Christopher Rufo, who helped kick off this controversy when he and fellow conservative Christopher Brunet leveled a round of accusations against Gay last month, has spent the past 24 hours doing a victory lap. It is this unseemly context that many academics are hung up on: In their minds, a college president succumbed to conservative pressure. And this fact is melting their brains and obliterating their standards for professional conduct. As Harvard Law’s own Charles Fried told The New York Times, “It’s part of this extreme right-wing attack on elite institutions.” And: “If it came from some other quarter, I might be granting it some credence … But not from these people.” Although the donor revolt and conservative pressure campaigns on elite universities—and, more important, public universities—are deeply worrying, the response of some faculty members to this plagiarism scandal is bound to make things worse.

See “Harvard Corporation”

“Report to the Harvard Governing Boards on Aspects of the Board of Overseers.” See the subsection entitled “Comparison with peer institutions” that begins on page 9.

Regardless of the exact list of powers (hard and soft) that each board possesses, they are both boards, distinct from administrations. Their role is broad oversight, not the daily operation of Harvard. From Harvard University Board of Overseers Expectations of Service:

…the Overseers’ role is one of oversight, not management, and exercising that responsibility in ways that respect the difference between serving as a board member and serving in an executive capacity.

“Indifference” here also includes the phenomenon where the HAA emails alumni regularly, but only hears back from a small portion of them. In those cases, they understandably choose to engage with those who engage with them! This isn’t a bad move at all, especially when you have limited time and resources. Why go after the 90% of alumni who don’t reach out to you, when you can spend your time with the 10% who do? The answer: just emailing them isn’t enough. If the HAA had stood up a skunkworks of engagement, and really tried their best to get higher engagement, then I would understand their current approach. But, as far as I know, they have not done this. So the onus is on them to try harder, and to try different things.

Harvard alumni vote concurrently for both the Board of Overseers and the Harvard Alumni Association’s Elected Director positions. In this post I am only reviewing the numbers for the Board of Overseers elections.

“Five New Members Elected to Harvard Board of Overseers,” The Harvard Crimson, accessed January 31, 2024.

Overseers elections are concurrent with Harvard Alumni Association Board of Directors Elected Directors elections, but this post focuses on the Overseers. To read more about the changes in 2016-2017, and 2018-2019, read this 2016 piece from Harvard Magazine. Also: the elections are numbered that way because the whole process tracks the academic year, not the calendar year. So the election that terminates in May 2017 will have procedurally begun in fall 2016.

“Harvard Reforms Overseer Election,” Harvard Magazine (Sept 1, 2016)

And others. Now—maybe you think there should be this much friction between alumni and casting their votes. But I do not think that’s an argument that anyone is making.

“Report to the Harvard Governing Boards on Aspects of the Board of Overseers,” p.19 (July 31, 2020)

I’ve written about my approach to teaching and political epistemics here:

“Thoughts on The Pedagogy of Politics” (April 2022)

“The Politics Cold Start Problem” (Dec 2022)

“The Standard Disclaimer: Avoid the Cold Start Problem and the Curse of Knowledge” (Dec 2022)

“A Challenge of Teaching Government & Politics” (Dec 2023)

“Atlantis on the Hudson,” footnote 7 (Feb 2022)

The Harvard Alumni Association fails in many similar respects.

If you ask me “what needs to be done?” I have a list as long as my arm. Not only to university governance, but to its pedagogy and academic program generally. But I’m not an armchair critic. For example, I think education in government should be different, so I built a civics school, which I’m now expanding into established institutions.